When is it possible to record from inside the human brain?

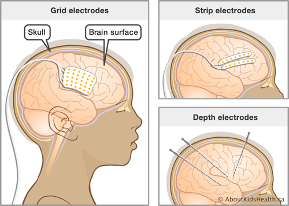

The goal of cognitive neuroscience is to understand how brain activity gives rise to cognition. However, researchers cannot measure activity inside the brain without performing neurosurgery, which would not be ethical or safe to do in healthy human volunteers. So, researchers are often limited to measuring brain activity indirectly from outside the head. However, in special situations, we do have the opportunity to directly record activity from a human brain. The procedure is known as intracranial recording, in which electrodes are placed inside of a hospital patient’s brain. These electrodes measure brain activity while the patient rests, sleeps, talks, or performs a behavioral experiment.

The goal of cognitive neuroscience is to understand how brain activity gives rise to cognition. However, researchers cannot measure activity inside the brain without performing neurosurgery, which would not be ethical or safe to do in healthy human volunteers. So, researchers are often limited to measuring brain activity indirectly from outside the head. However, in special situations, we do have the opportunity to directly record activity from a human brain. The procedure is known as intracranial recording, in which electrodes are placed inside of a hospital patient’s brain. These electrodes measure brain activity while the patient rests, sleeps, talks, or performs a behavioral experiment.

Why would someone undergo such an invasive procedure? These patients have intractable epilepsy, meaning that they have severe seizures which cannot be controlled by medications. Seizures often arise from one area of the brain, after which activity spreads and causes symptoms such as uncontrolled body movements or loss of consciousness. When all other medical treatments have failed, the best remaining option is sometimes to remove the part of the brain where seizures start.

To help determine which part of the brain to remove, neurosurgeons implant electrodes inside the patient’s brain and wait for seizures to happen. This can take 1-2 weeks, while the patient lies in their hospital bed. We as researchers visit the patients during this time and ask if they want to participate in experiments. They are often restless or bored, so are happy to be distracted with fun tasks. These epileptic patients provide an incredible and rare opportunity to directly measure human brain activity and allow us to ask new questions about the relationship between brain and behavior.

-Brynn Sherman

Psychology is full of interesting questions and interesting ways to test them. A lot of the research in our lab involves behavioral experiments. We call them “behavioral” because they examine human behavior as the primary measure of interest, as opposed to other methods used in the lab that study brain function or brain damage. There are lots of different tasks used in behavioral experiments and each one differs in terms of what you are asked to do.

Psychology is full of interesting questions and interesting ways to test them. A lot of the research in our lab involves behavioral experiments. We call them “behavioral” because they examine human behavior as the primary measure of interest, as opposed to other methods used in the lab that study brain function or brain damage. There are lots of different tasks used in behavioral experiments and each one differs in terms of what you are asked to do. A lot of experiments in the lab use a tool called Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). This powerful tool allows us to study how the human brain works. An MRI machine (or “scanner”) is essentially a huge and very strong magnet. This magnetic field acts on the atoms in the brain. In particular, it changes how those atoms rotate (or spin). When there’s not a magnetic field, all of the atoms spin in random directions. But in a uniform magnetic field, the atoms spin in the same direction. Then, during an MRI scan, we introduce brief bursts of radio waves (like a radio station) that knock the atoms out of alignment. We measure how many of the waves are resonated back out of the brain as the atoms realign.

A lot of experiments in the lab use a tool called Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). This powerful tool allows us to study how the human brain works. An MRI machine (or “scanner”) is essentially a huge and very strong magnet. This magnetic field acts on the atoms in the brain. In particular, it changes how those atoms rotate (or spin). When there’s not a magnetic field, all of the atoms spin in random directions. But in a uniform magnetic field, the atoms spin in the same direction. Then, during an MRI scan, we introduce brief bursts of radio waves (like a radio station) that knock the atoms out of alignment. We measure how many of the waves are resonated back out of the brain as the atoms realign.